Seeking Not Running

By Reverend Rebecca Bryan

Thank you, Diane, for your beautiful and moving Journey of Faith. You have given us a huge gift, and I wanted to be sure we took the time and learned from that gift. I’m sure many of us can relate to your story of religious upbringing, longing, and seeking. So many people come to Unitarian Universalism as adults, with their own religious stories, which are too often filled with pain, betrayal, and disconnection. I’m also sure that many, if not all of us, identify with your story of family history, secrets, and shame. I know that all of us either share or are inspired by your experience with redemption and forgiveness as it relates to those early religious and family stories.

As I was thinking about this service and the need for us all to honor and learn from our past, choosing what we wish to take forward and what we want to leave behind, I realized that what we need to do this well are tools—specific, concrete suggestions of things people have found helpful in their process of spiritual seeking and integrating their past. There are many approaches to this, and all of us have found some ways more effective than others.

Today, I want to focus on writing, and specifically letter writing, as a way to support our spiritual journeys and integrate our past.

Letter writing: what comes to your mind when I say that?

I think of letters to and from my grandmother, one of which sits framed on the bookshelf across from my desk. I also remember a candle and wax seal my aunt and uncle gave me for Christmas one year when I was eleven. I can still feel the square buttercup colored candle, its wax dripping perfectly onto the envelope, and the soft squish as I pressed into the seal. More recently when I think of letters, I remember my dining room table covered with cards and letters from friends and congregants when I was recovering from a bicycle accident.

Letters, cards—they serve such important roles in our lives. They can be used to thank people, keep in touch, record history, or just say hello.

Letters have changed the course of history. Colin Salter in his book 100 Letters that Changed the World tells of Galileo’s letter in 1610 that explained the first sighting of the moons of Jupiter. Thomas Jefferson’s letter to his nephew in 1787 advised his nephew to question the existence of God. And Nelson Mandela’s letter sent the South African prime minister an ultimatum in 1961.1

Who can forget Martin Luther King, Junior’s 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail” or the letter printed by The New York Times in 2018 signed by more than three hundred women working in the entertainment industry calling for the end to sexual harassment and gender inequality?

Most recently, Italian novelist Francesca Melandri, who had been in lockdown due to COVID–19 for more than three weeks, wrote a letter to fellow Europeans entitled “From Your Future.” It begins, “I am writing to you from Italy, which means I am writing from your future.” Melandri went on to say many things foretelling what this time of self-quarantine will include. She said that people would:

…eat. Not just because it will be one of the few last things that you can still do.

…find dozens of social networking groups with tutorials…You will join them all, then ignore them completely after a few days. You’ll eat again.

You will not sleep well.

You will ask yourselves what is happening to democracy.

You will miss your adult children like you never have before; the realisation that you have no idea when you will ever see them again will hit you like a punch in the chest.

Your children will be schooled online. They’ll be horrible nuisances; they’ll give you joy.

You will try not to think about the lonely deaths inside the ICU.

You’ll want to cover with rose petals all medical workers’ steps.

You will be told that society is united in a communal effort, that you are all in the same boat.

It will be true.

This experience will change for good how you perceive yourself as an individual part of a larger whole.2

There’s more, and I highly recommend reading all of it.

Letters of famous people are collected and printed, often posthumously. In preparation for this sermon, I’ve read or revisited Flannery O’Connor’s letters The Habit of Being, Sister Love: The Letters of Audre Lorde and Pat Parker, Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet that our reading came from this morning, and the letters between Emily Dickinson and Reverend Thomas Wentworth Higginson, an earlier minister of this church.

I need to acknowledge that this gift of letter writing is a privilege. Proliteracy, an organization dedicated to improving literacy rates across the globe, reports that about thirty-six million adults in the United States, and almost eight hundred million worldwide, struggle with basic reading, writing and math skills.3

Letter writing, whether used for communicating with family or friends, making a public statement, or organizing, is critical and something worthy of continuing. In my own experience, it seems to be going through a slump. It is no longer customary to receive or write thank–you letters for job interviews or for networking. Even thank–you notes for gifts given are sadly on the decline. The good old–fashioned letter as a means of correspondence is especially rare.

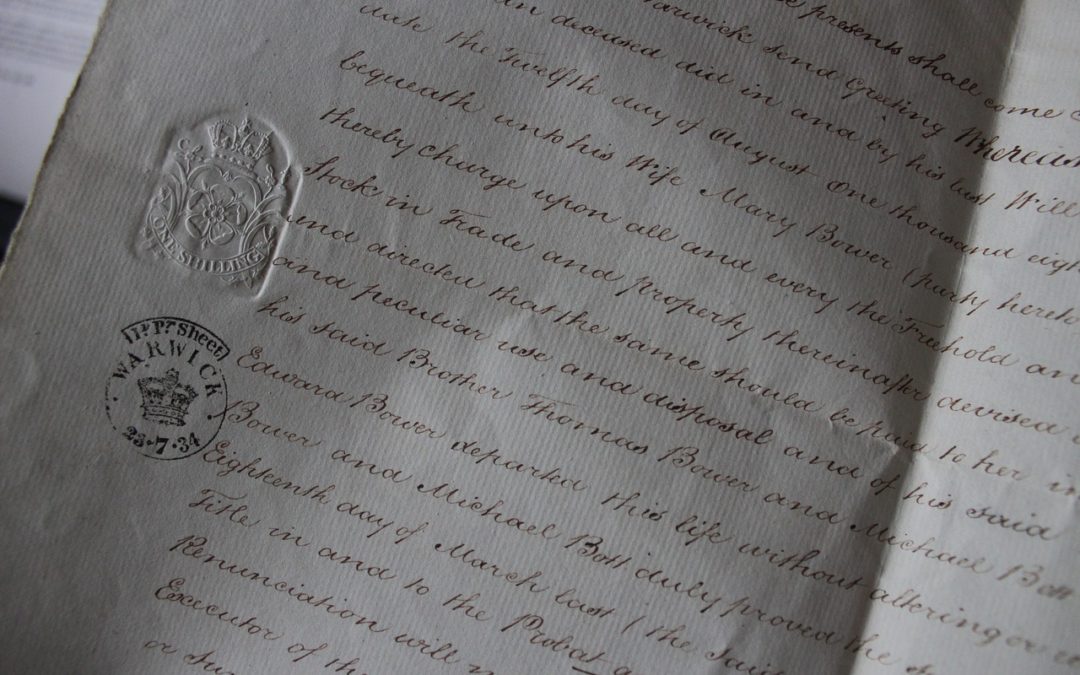

Letter writing is a means of documenting history or communicating, and it is so much more. It turns an event, which is something that happens, into an experience, which is an event we’ve found meaning in. Writing is also a spiritual practice that supports our emotional wellbeing and care of our soul.

In her book Writing the Sacred Journey Elizabeth Andrew says that people write because “writing brings them nearer to the ineffable essence of life.”4 Though she is referring to spiritual memoirists, I believe her statement applies to all writing, including letter writing. One of the most powerful letters I ever wrote was to my father–in–law after his death. The letter was transformative for my spiritual journey. Andrew goes on to say, “You can only discover why a story matters by telling it or writing it.”5 Something important happens in the act of transmission. The writing allows the story itself to speak to us, reveal its hidden gifts and opportunities. It is also much more accurate than relying on our memory, which for all of us is inclined to alter stories over time.

Imagine if we had letters from our ancestors, all of them, or had letters from different ages and stages of our life, written to ourselves or others. The power of narrative history is deeply personal and moving. It makes history real.

This led me to think…we can do this here. We can write letters during this time of COVID-19 to our family members and friends and to the descendants of this church. We can make a time capsule filled with personal narratives that will give people fifty to one hundred years from now a firsthand account of what these times were like.

I’m not the only one excited by this idea. So is Sharon Spieldenner, Senior Librarian and Archivist of the Newburyport Public Library Archival Center. She and I spoke last Wednesday, thanks to the support of Linda Tulley and Linda Buddenhagen. As some of you may know, the Newburyport Library Archival Center holds the historic records of the First Religious Society. These include sermons, meeting minutes, and records of births, baptisms, and weddings. The library would love to hold this future–looking time capsule we make and add it to our other church records. The archival center is also collecting records of this time in Newburyport’s history including Mayor Holaday’s speeches, notes from the newspaper, and photos.

You are all invited to join us, members and friends. We want to have all ages do this! To capture a full picture of this time in history, we want to include what it is like for our school–age children, teens, parents, and elders.

You can write a letter documenting what you are experiencing, thinking about, and feeling. Consider sharing how this experience is impacting you and your family, and what you are observing in yourself, the city, and the world. Write whatever moves you.

Imagine people generations from now reading your letter. What will we want them to know and understand? What will help them in their spiritual seeking? How can your letter help them to remember and learn from the past, even as they accept their present and dream of their future? What a gift we will be creating!

You can send the letter to the church, marked “time capsule” or you can email your letter to timecapsule@frsuu.org. This time capsule and letter–writing project is just one way that we can make meaning out of this time. It is one tool to support us individually and collectively, in our seeking and desire to find hope and create connection.

In a moment we are going to sing our closing hymn “Blue Boat Home.” When UU songwriter Peter Mayer was interviewed about this song, he spoke of how he grew from his Catholic religious upbringing to becoming a Unitarian Universalist. In reference to his spirituality today, he said, “My interest lies more in how we as humans can cultivate a deeper connection to each other, to the world around us, and to the story of the universe itself.”6 What better time to be cultivating that connection than now?

As Malendri wrote in her letter, “This experience will change for good how you perceive yourself as an individual part of a larger whole…you are all in the same boat…”7We are in the same boat my friends, and for that we can be grateful.

Amen and blessed be.

Questions to ponder, discuss and hold…

What is a question you have for your ancestors?

What and how are you seeking in your life?

Who will you write a letter to, and why?