Finding Integrity in Jazz

By Tom Stites, guest speaker

The jazz great John Coltrane’s words and music reveal him to have been a profoundly religious person. We UUs are a religion of seekers, but almost all of us are pikers compared with Coltrane. His grandfather was an A.M.E. minister. He explored Hinduism and Zen Buddhism, among many other religions and philosophies, and he married a Muslim – Naima, for whom the song we just heard was named. He considered his religion universal.

There’s no evidence that Coltrane ever considered Unitarian Universalism, so we can make no claim on him, but I ask that we recognize him as a kindred spirit and welcome his wisdom into our sanctuary this morning. He has much to share.

Coltrane presented his masterpiece 1964 album, A Love Supreme, as a religious statement in four parts. Note that we did not select any of the music from the album for this morning’s service. The music is too personal, too much of his spirit, too much the expression of where he and his quartet were when the recording was made 55 years ago. The recording was made in a studio and the only known live performance was in Europe a few months later. In some ways not playing this music is a mark of respect. The album still sells and sells but almost no musicians now play the music from it.

Almost.

There’s one exception – the music is routinely played in worship at the Church of St. John Coltrane in San Francisco, which is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year. The congregation is one of about 15 affiliated with the African Orthodox Church, which was founded by breakaway black Episcopalians in 1921 and once was much larger. The Coltrane church’s music program features a rotating ensemble of jazz musicians who welcome visiting musicians to sit in. Just so you know: Worshiping there is on my bucket list.

My friend the religion journalist and jazz lover Samuel G. Freedman wrote in The New York Times that “the Coltrane church is not a gimmick or a forced alloy of nightclub music and ethereal faith. Its message of deliverance through divine sound is actually quite consistent with Coltrane’s own experience and message.”

The liner notes for the A Love Supreme album include a poem to God that Coltrane wrote. It is a stream not so much of consciousness but of spirit, a stream of praise and gratitude. He said he believed in all religions but it is clear that he was a theist and that the God he knew was omnipotent. Toward the end of the poem, Coltrane writes,

God breathes through us so completely… so gently we hardly feel it… yet, it is our everything. Thank you God.

So what can we, as religious people who tend to be quite a bit less Universalist than Coltrane was, and quite a bit less theist, what can we learn from this musical and spiritual genius? And what can we learn from the music he so shaped, from jazz, our nation’s greatest indigenous art form?

Before we dive into that question, let’s pause for a bit. I want to make sure you know that I take John Coltrane with great seriousness. His religious stature rivals his stature as a musician, which is towering. All of his wisdom, musical and religious, is something to consider with respect. He probably comes closer to being a real saint than anyone whose words I’ve quoted in the almost 60 jazz services I’ve preached. I am humbled that his wisdom is up here in the pulpit with me today, and that I have the opportunity to share it with you.

Coltrane didn’t write that much – he was, after all, a musician – yet his words can be found in the liner notes on the backs of his albums and in interviews with writers. There are enough of them that as this sermon proceeds I’ll be saying And Coltrane Says several times.

So let me start answering the question of what we can learn from Coltrane and from jazz by pointing out that at the core of UU theology is a striving for integrity in the fullest sense of the word – for integration of the mind and heart and spirit, for wholeness, for oneness.

A yearning for this is what has drawn me to church for all these years. This yearning has also drawn me to jazz, whose beauty is an expression of the integrity of the players and their bands.

I used to say I was searching for ways to bring my life into balance, but balance is a limited word – the balance scale has only two sides. Life is more complicated than that, and integrity is a much more spacious word, spacious enough for everything to come together in it.

For theists, the search for integrity extends to striving for oneness with God. For nontheists like me, it extends to striving for oneness with the ultimate forces of the universe.

And Coltrane said, “Always there is the need to keep purifying these feelings and sounds so that we can really see what we’ve discovered in its pure state, so that we can see more and more clearly what we are.”

Isn’t it the most fundamental of religious quests to see most clearly what we are, to see what makes us unique, to see what our unique gift is? And then, once we’ve figured that out, isn’t it our religious calling to devote our energy to delivering this gift to the world? Can there be any deeper form of integrity?

And Coltrane said, “My music is the spiritual expression of what I am – my faith, my knowledge, my being.”

Whatever our personal theologies, the search for integrity, for seeing “more and more clearly what we are,” extends to striving for oneness with ultimate truth. It is this search for truth that propels us along our individual religious paths, and we know that sometimes the terrain can be pretty rough.

Think how much easier life would be if the same ultimate truth were revealed to everybody and there would be no more argument about it? But we know from our own lived experience that this is not the case, and this knowledge compels us on our search – and it compels us to muster respect for others whose paths differ from ours. The integrity we seek, the oneness, is the “unit” in Unitarian and the “universal” in Universalist.

Where people come together, UU theology is about the struggle to achieve what theologians call right relationship. This term is centuries old and rich with meaning: When people are in right relationship, they are striving for mutual trust, respect and understanding.

Isn’t this what a jazz band does? Think of the Vespers Band as a tiny, intense congregation. The players must pay close attention to one another so they can support each other as they improvise – based on the shared values of tempo, rhythm, key, and chord changes – to achieve beauty, a common good. That’s what Lark and Danny and Susan and Mike and Tomas have been doing for us this morning, in the holy presence of the spirit of St. John Coltrane. And we are all better for hearing what their right relationship produces.

When we pay attention to our communities and to the world in the way jazz musicians must pay attention to one another, there’s no way to escape compassionate response for so many people whose world is a world of hurt. Compassion inspires engagement, and engagement demands justice. This leads us to work together for a better world.

And Coltrane said, “When there is something that we feel should be better, we must exert effort to try and make it better. So it’s the same socially, musically, politically, in any department of our lives.”

And because the forces of injustice never willingly give up their power, creating a better world really does takes creativity. The forces of injustice are crafty and relentless, and we have to be seriously inventive to figure out ways to overcome them.

And Coltrane said, “I know that there are bad forces, forces that bring suffering to others and misery to the world, but I want to be the opposite force. I want to be the force which is truly for good.”

And he added, “I think music is an instrument. It can create the initial thought patterns that can change the thinking of the people.”

When the world of hurt invades our own lives, members of our band, which is to say our fellow parishioners, can be expected to bring their compassion to us because they are paying attention. And here, just to improvise a bit, I’m going to quote a wise person other than John Coltrane – the late Unitarian religious scholar, the Rev. John F. Hayward. He said, “A song of sadness, defiance, even despair, by virtue of being a song . . . is the beginning of redemption.”

And by paying attention to others in our congregation, we notice their need and act for them. That’s right relationship.

And Coltrane said, “Overall, I think the main thing a musician would like to do is give to the listener the many wonderful things he knows of and senses in the universe. . . . That’s what I would like to do. I think that’s one of the greatest things you can do in life, and we all try to do that in some way. The musician’s is through his music.”

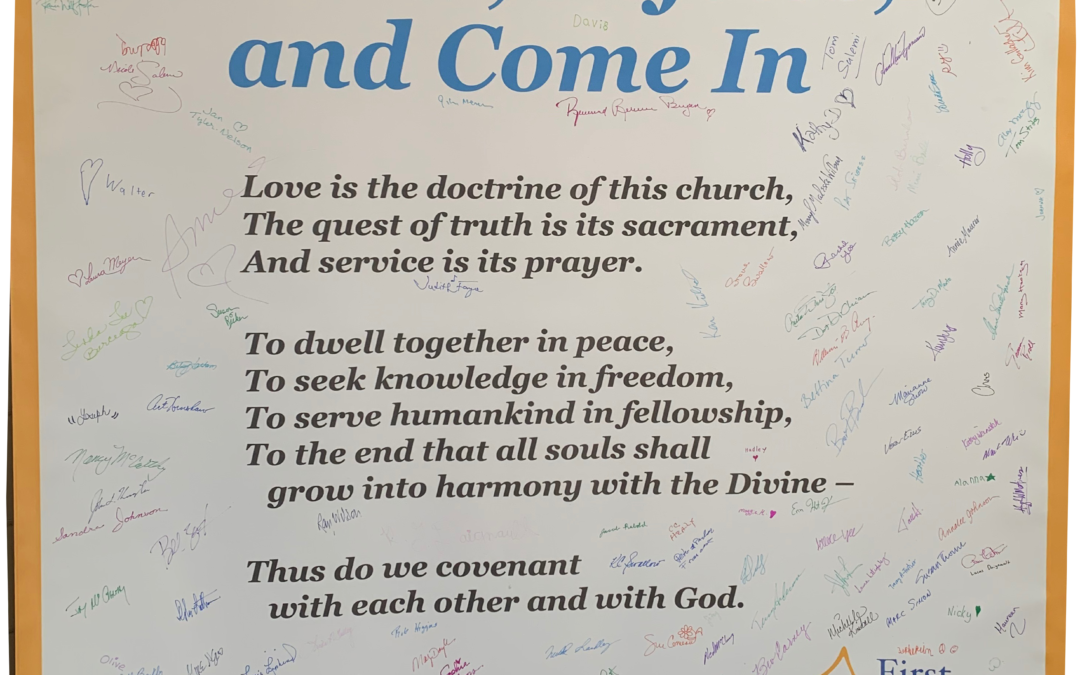

When people in right relationship have conflict, as all people inevitably do, it is productive conflict, meaning that resolving it leads to personal growth, to deeper truth, to greater integrity. This is how, as we say in our Affirmation of Faith every Sunday, we grown into harmony with the divine.

And Coltrane said, “When you begin to see the possibilities of music, you desire to do something good for people, to help humanity free itself.”

It breaks my heart to tell you that John Coltrane died of liver cancer when he was only 40, only three years after recording A Love Supreme. Can you imagine the impact he might have had if he’d lived to a ripe old age? The impact of his sainthood?

But let us rejoice that his music lives on, not only in his recordings and in his profound contributions to the theory of chord changes, but in his influence on the generations of musicians who have followed him. And his powerful spirit lives on, not only in the Church of St. John Coltrane in San Francisco but also in this sanctuary this morning. And in the hearts of all who hear his music.

[Danny Harrington offers a brief improvisation on Naima.]

Amen.